Which of the Following Measures Can Only Government Action Effectively Implement?

Abstract

Assessing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-two is critical to inform time to come preparedness response plans. Here we quantify the impact of 6,068 hierarchically coded NPIs implemented in 79 territories on the effective reproduction number, R t , of COVID-19. We propose a modelling approach that combines four computational techniques merging statistical, inference and artificial intelligence tools. Nosotros validate our findings with two external datasets recording 42,151 boosted NPIs from 226 countries. Our results bespeak that a suitable combination of NPIs is necessary to curb the spread of the virus. Less disruptive and costly NPIs can be as constructive as more intrusive, desperate, ones (for example, a national lockdown). Using land-specific 'what-if' scenarios, we assess how the effectiveness of NPIs depends on the local context such equally timing of their adoption, opening the mode for forecasting the effectiveness of future interventions.

Main

In the absence of vaccines and antiviral medication, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) implemented in response to (emerging) epidemic respiratory viruses are the merely selection available to delay and moderate the spread of the virus in a population1.

Confronted with the worldwide COVID-xix epidemic, most governments accept implemented bundles of highly restrictive, sometimes intrusive, NPIs. Decisions had to be taken under chop-chop changing epidemiological situations, despite (at least at the very start of the epidemic) a lack of scientific testify on the individual and combined effectiveness of these measures2,3,4, degree of compliance of the population and societal impact.

Government interventions may cause substantial economic and social costs5 while affecting individuals' behaviour, mental wellness and social securityhalf dozen. Therefore, knowledge of the virtually effective NPIs would allow stakeholders to judiciously and timely implement a specific sequence of central interventions to combat a resurgence of COVID-19 or any other future respiratory outbreak. Because many countries rolled out several NPIs simultaneously, the challenge arises of disentangling the impact of each individual intervention.

To engagement, studies of the state-specific progression of the COVID-19 pandemic7 take mostly explored the independent effects of a single category of interventions. These categories include travel restrictions2,8, social distancing9,ten,11,12 and personal protective measures13. Additionally, modelling studies typically focus on NPIs that directly influence contact probabilities (for example, social distancing measuresxviii, social distancing behaviours 12, cocky-isolation, school closures, bans on public eventsxx and so on). Some studies focused on a single state or even a boondocksxiv,15,16,17,18 while other research combined data from multiple countries but pooled NPIs into rather broad categories15,19,twenty,21, which somewhen limits the cess of specific, potentially critical, NPIs that may be less costly and more constructive than others. Despite their widespread apply, relative ease of implementation, broad selection of available tools and their importance in developing countries where other measures (for example, increases in healthcare capacity, social distancing or enhanced testing) are difficult to implement22, little is currently known about the effectiveness of different hazard-advice strategies. An accurate assessment of communication activities requires information on the targeted public, means of communication and content of the message.

Using a comprehensive, hierarchically coded dataset of 6,068 NPIs implemented in March–April 2022 (when about European countries and Us states experienced their start infection waves) in 79 territories23, hither nosotros analyse the bear on of government interventions on R t using harmonized results from a multi-method approach consisting of (1) a example-control analysis (CC), (two) a step office approach to LASSO time-series regression (LASSO), (three) random forests (RF) and (four) transformers (TF). We contend that the combination of four unlike methods, combining statistical, inference and artificial intelligence classes of tools, also allows assessment of the structural uncertainty of individual methods24. Nosotros likewise investigate country-specific control strategies as well equally the touch on of selected land-specific metrics.

All the in a higher place approaches (i–4) yield comparable rankings of the effectiveness of dissimilar categories of NPIs across their hierarchical levels. This remarkable agreement allows us to place a consensus prepare of NPIs that atomic number 82 to a significant reduction in R t . We validate this consensus set using two external datasets covering 42,151 measures in 226 countries. Furthermore, we evaluate the heterogeneity of the effectiveness of private NPIs in different territories. We find that the time of implementation, previously implemented measures, different governance indicators25, as well as man and social development touch the effectiveness of NPIs in countries to varying degrees.

Results

Global arroyo

Our main results are based on the Complexity Science Hub COVID-19 Command Strategies Listing (CCCSL)23. This dataset provides a hierarchical taxonomy of 6,068 NPIs, coded on 4 levels, including viii broad themes (level i, L1) divided into 63 categories of individual NPIs (level 2, L2) that include >500 subcategories (level iii, L3) and >ii,000 codes (level 4, L4). Nosotros first compare the results for NPI effectiveness rankings for the 4 methods of our arroyo (1–4) on L1 (themes) (Supplementary Fig. 1). A clear picture emerges where the themes of social distancing and travel restrictions are meridian ranked in all methods, whereas environmental measures (for example, cleaning and disinfection of shared surfaces) are ranked to the lowest degree effective.

We next compare results obtained on L2 of the NPI dataset—that is, using the 46 NPI categories implemented more five times. The methods largely agree on the list of interventions that have a significant event on R t (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The individual rankings are highly correlated with each other (P = 0.0008; Methods). Vi NPI categories show significant impacts on R t in all 4 methods. In Supplementary Table 1 nosotros list the subcategories (L3) belonging to these consensus categories.

The left-hand panel shows the combined 95% confidence intervals of ΔR t for the most effective interventions across all included territories. The heatmap in the right-hand panel shows the respective Z-scores of mensurate effectiveness as determined by the four different methods. Grey indicates no significantly positive upshot. NPIs are ranked according to the number of methods agreeing on their impacts, from top (significant in all methods) to bottom (ineffective in all analyses). L1 themes are color-coded as in Supplementary Fig. ane.

A normalized score for each NPI category is obtained past rescaling the event within each method to range betwixt zero (least effective) and i (most constructive) and so averaging this score. The maximal (minimal) NPI score is therefore 100% (0%), pregnant that the measure out is the about (least) effective measure in each method. We evidence the normalized scores for all measures in the CCCSL dataset in Extended Data Fig. i, for the CoronaNet dataset in Extended Data Fig. 2 and for the WHO Global Dataset of Public Health and Social Measures (WHO-PHSM) in Extended Data Fig. 3. Among the six full-consensus NPI categories in the CCCSL, the largest impacts on R t are shown past small gathering cancellations (83%, ΔR t between −0.22 and –0.35), the closure of educational institutions (73%, and estimates for ΔR t ranging from −0.15 to −0.21) and border restrictions (56%, ΔR t betwixt −0.057 and –0.23). The consensus measures also include NPIs aiming to increase healthcare and public wellness capacities (increased availability of personal protective equipment (PPE): 51%, ΔR t −0.062 to −0.thirteen), individual movement restrictions (42%, ΔR t −0.08 to −0.xiii) and national lockdown (including stay-calm order in The states states) (25%, ΔR t −0.008 to −0.14).

We find 14 additional NPI categories consensually in iii of our methods. These include mass gathering cancellations (53%, ΔR t betwixt −0.13 and –0.33), risk-communication activities to inform and educate the public (48%, ΔR t between –0.18 and –0.28) and government aid to vulnerable populations (41%, ΔR t between −0.17 and –0.18).

Among the to the lowest degree constructive interventions we find: government actions to provide or receive international assist, measures to enhance testing capacity or improve example detection strategy (which tin can be expected to lead to a short-term ascent in cases), tracing and tracking measures besides as land border and airport health checks and environmental cleaning.

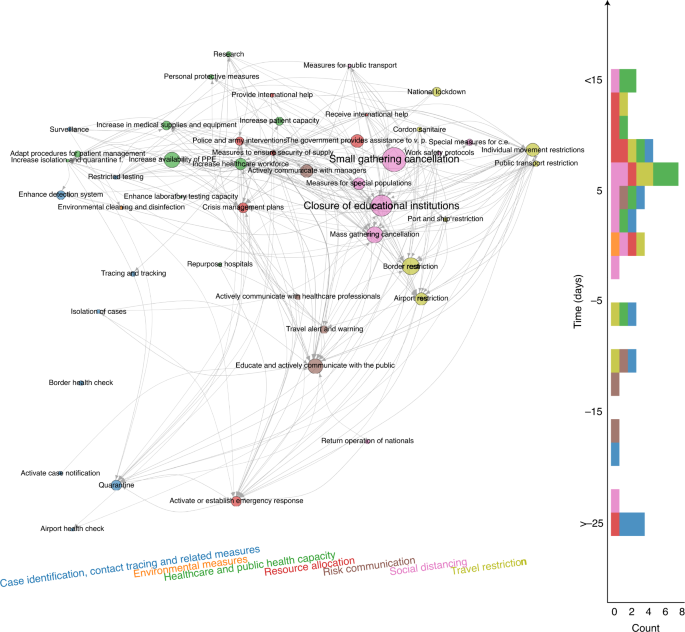

In Fig. 2 we testify the findings on NPI effectiveness in a co-implementation network. Nodes correspond to categories (L2) with size beingness proportional to their normalized score. Directed links from i to j indicate a trend that countries implement NPI j after they have implemented i. The network therefore illustrates the typical NPI implementation sequence in the 56 countries and the steps within this sequence that contribute most to a reduction in R t . For case, there is a design where countries first cancel mass gatherings before moving on to cancellations of specific types of small-scale gatherings, where the latter associates on average with more substantial reductions in R t . Education and active communication with the public is i of the most effective 'early on measures' (implemented around xv days before 30 cases were reported and well before the majority of other measures comes). Near social distancing (that is, closure of educational institutions), travel brake measures (that is, individual movement restrictions like curfew and national lockdown) and measures to increase the availability of PPE are typically implemented within the first 2 weeks after reaching 30 cases, with varying impacts on R t ; see likewise Fig. 1.

Nodes are categories (L2), with colours indicating the theme (L1) and size being proportional to the boilerplate effectiveness of the intervention. Arrows from nodes i to j denote that those countries which have already implemented intervention i tend to implement intervention j later in time. Nodes are positioned vertically according to their average time of implementation (measured relative to the day where that country reached 30 confirmed cases), and horizontally according to their L1 theme. The stacked histogram on the right shows the number of implemented NPIs per time period (epidemic historic period) and theme (colour). v.p., vulnerable populations; c.e., certain establishments; quarantine f., quarantine facilities.

Within the CC approach, we can farther explore these results on a effectively hierarchical level. We evidence results for xviii NPIs (L3) of the risk-advice theme in Supplementary Information and Supplementary Tabular array two. The nearly effective communication strategies include warnings confronting travel to, and return from, high-risk areas (ΔR CC t = −0.fourteen (one); the number in parenthesis denotes the standard mistake) and several measures to actively communicate with the public. These include to encourage, for case, staying at home (ΔR CC t = −0.14 (1)), social distancing (ΔR CC t = −0.20 (1)), workplace safety measures (ΔR CC t = −0.18 (2)), cocky-initiated isolation of people with mild respiratory symptoms (ΔR CC t = −0.19 (2)) and information campaigns (ΔR CC t = −0.xiii (1)) (through various channels including the press, flyers, social media or telephone messages).

Validation with external datasets

Nosotros validate our findings with results from two external datasets (Methods). In the WHO-PHSM dataset26 nosotros find seven full-consensus measures (agreement on significance by all methods) and 17 farther measures with three agreements (Extended Data Fig. 4). These consensus measures show a large overlap with those (three or four matches in our methods) identified using the CCCSL, and include top-ranked NPI measures aiming at strengthening the healthcare system and testing capacity (labelled as 'scaling up')—for instance, increasing the healthcare workforce, purchase of medical equipment, testing, masks, financial support to hospitals, increasing patient capacity, increasing domestic production of PPE. Other consensus measures consist of social distancing measures ('cancelling, restricting or adapting private gatherings outside the home', adapting or closing 'offices, businesses, institutions and operations', 'cancelling, restricting or adapting mass gatherings'), measures for special populations ('protecting population in closed settings', encompassing long-term care facilities and prisons), schoolhouse closures, travel restrictions (restricting entry and get out, travel advice and warning, 'endmost international land borders', 'entry screening and isolation or quarantine') and individual movement brake ('stay-at-habitation order', which is equivalent to confinement in the WHO-PHSM coding). 'Wearing a mask' exhibits a significant impact on R t in three methods (ΔR t between −0.018 and –0.12). The consensus measures also include fiscal packages and general public awareness campaigns (as function of 'communications and engagement' deportment). The least effective measures include active case detection, contact tracing and environmental cleaning and disinfection.

The CCCSL results are also compatible with findings from the CoronaNet dataset27 (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6). Analyses show 4 full-consensus measures and thirteen further NPIs with an understanding of three methods. These consensus measures include heterogeneous social distancing measures (for example, restriction and regulation of non-essential businesses, restrictions of mass gatherings), closure and regulation of schools, travel restrictions (for example, internal and external border restrictions), individual movement restriction (curfew), measures aiming to increment the healthcare workforce (for example, 'nurses', 'unspecified health staff') and medical equipment (for example, PPE, 'ventilators', 'unspecified health materials'), quarantine (that is, voluntary or mandatory cocky-quarantine and quarantine at a government hotel or facility) and measures to increment public awareness ('disseminating information related to COVID-xix to the public that is reliable and factually accurate').

Twenty-three NPIs in the CoronaNet dataset do not show statistical significance in any method, including several restrictions and regulations of government services (for example, for tourist sites, parks, public museums, telecommunication), hygiene measures for public areas and other measures that target very specific populations (for case, certain age groups, visa extensions).

State-level approach

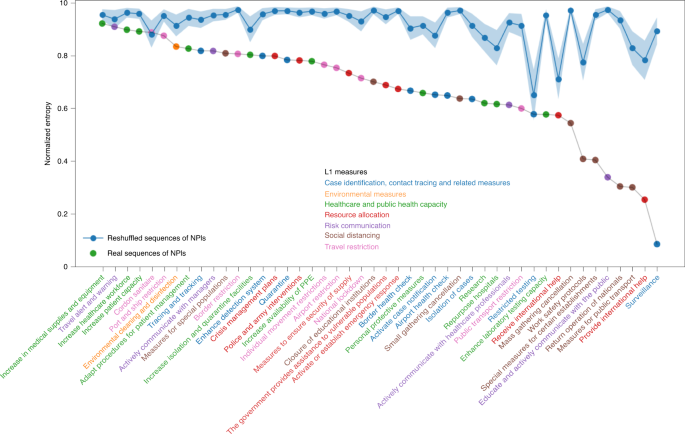

A sensitivity cheque of our results with respect to the removal of individual continents from the analysis also indicates substantial variations between world geographical regions in terms of NPI effectiveness (Supplementary Information). To further quantify how much the effectiveness of an NPI depends on the item territory (country or US state) where information technology has been introduced, we measure the heterogeneity of NPI rankings in different territories through an entropic arroyo in the TF method (Methods). Figure 3 shows the normalized entropy of each NPI category versus its rank. A value of entropy close to zero implies that the corresponding NPI has a similar rank relative to all other NPIs in all territories: in other words, the effectiveness of the NPI does non depend on the specific country or state. On the other hand, a loftier value of the normalized entropy signals that the performance of each NPI depends largely on the geographical region.

Each NPI is colour coded according to its theme of belonging (L1), equally indicated in the legend. The blue curve represents the same information obtained from a reshuffled dataset of NPIs.

The values of the normalized entropies for many NPIs are far from one, and are besides below the corresponding values obtained through temporal reshuffling of NPIs in each country. The effectiveness of many NPIs therefore is, outset, significant and, 2d, depends on the local context (combination of socio-economic features and NPIs already adopted) to varying degrees. In general, social distancing measures and travel restrictions show a loftier entropy (effectiveness varies considerably across countries) whereas case identification, contact tracing and healthcare measures show substantially less country dependence.

Nosotros further explore this interplay of NPIs with socio-economic factors by analysing the effects of demographic and socio-economical covariates, besides equally indicators for governance and human being and economical development in the CC method (Supplementary Information). While the effects of almost indicators vary across dissimilar NPIs at rather moderate levels, nosotros notice a robust trend that NPI effectiveness correlates negatively with indicator values for governance-related accountability and political stability (equally quantified past World Governance Indicators provided by the Earth Banking company).

Because the heterogeneity of the effectiveness of individual NPIs across countries points to a non-independence among unlike NPIs, the affect of a specific NPI cannot be evaluated in isolation. Since information technology is not possible in the real world to change the sequence of NPIs adopted, nosotros resort to 'what-if' experiments to place the nigh likely outcome of an artificial sequence of NPIs in each country. Within the TF arroyo, we selectively delete one NPI at a time from all sequences of interventions in all countries and compute the ensuing evolution of R t compared to the actual case.

To quantify whether the effectiveness of a specific NPI depends on its epidemic age of implementation, we study artificial sequences of NPIs constructed by shifting the selected NPI to other days, keeping the other NPIs fixed. In this manner, for each country and each NPI, we obtain a curve of the most probable change in R t versus the adoption time of the specific NPI.

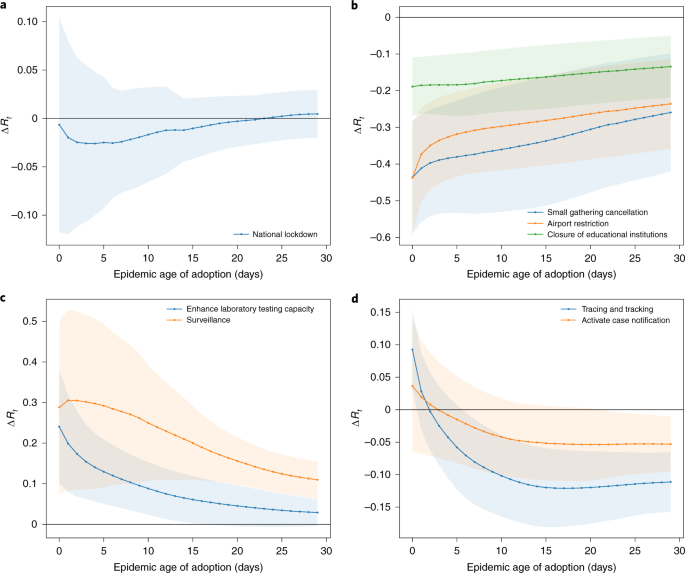

Figure four shows an instance of the results for a selection of NPIs (see Supplementary Information for a more extensive report on other NPIs). Each curve shows the average change in R t versus the adoption time of the NPI, averaged over the countries where that NPI has been adopted. Effigy 4a refers to the national lockdown (including stay-at-home lodge implemented in United states of america states). Our results prove a moderate effect of this NPI (low alter in R t ) as compared to other, less drastic, measures. Effigy 4b shows NPIs with the design 'the earlier, the meliorate'. For those measures ('closure of educational institutions', 'pocket-size gatherings counterfoil', 'airport restrictions' and many more shown in Supplementary Information), early adoption is always more beneficial. In Fig. 4c, 'enhancing testing chapters' and 'surveillance' exhibit a negative touch on (that is, an increase) on R t , presumably related to the fact that more testing allows for more cases to exist identified. Finally, Fig. 4d, showing 'tracing and tracking' and 'activate case notification', demonstrates an initially negative issue that turns positive (that is, toward a reduction in R t ). Refer to Supplementary Information for a more comprehensive analysis of all NPIs.

a, National lockdown (including stay-at-home lodge in US states). b, A selection of iii NPIs displaying 'the earlier the better' behaviour—that is, their touch on is enhanced if implemented at before epidemic ages. c, Heighten laboratory testing chapters and Surveillance. d, Tracing and tracking and Activate instance notification. Negative (positive) values indicate that the adoption of the NPI has reduced (increased) the value of R t . Shaded areas denote due south.d.

Discussion

Our study dissects the entangled packages of NPIs23 and quantifies their effectiveness. We validate our findings using three different datasets and 4 independent methods. Our findings suggest that no NPI acts as a silver bullet on the spread of COVID-19. Instead, we identify several decisive interventions that significantly contribute to reducing R t below one and that should therefore be considered equally efficiently flattening the curve facing a potential 2nd COVID-nineteen wave, or any like future viral respiratory epidemics.

The most effective NPIs include curfews, lockdowns and closing and restricting places where people gather in smaller or large numbers for an extended flow of time. This includes small gathering cancellations (closures of shops, restaurants, gatherings of 50 persons or fewer, mandatory abode working and then on) and closure of educational institutions. While in previous studies, based on smaller numbers of countries, school closures had been attributed as having petty issue on the spread of COVID-19 (refs. 19,20), more contempo evidence has been in favour of the importance of this NPI28,29; school closures in the Usa accept been institute to reduce COVID-nineteen incidence and mortality past near 60% (ref. 28). This outcome is too in line with a contact-tracing report from South Korea, which identified adolescents anile 10–nineteen years every bit more likely to spread the virus than adults and children in household settingsthirty. Individual movement restrictions (including curfew, the prohibition of gatherings and movements for not-essential activities or measures segmenting the population) were also amongst the top-ranked measures.

However, such radical measures take adverse consequences. School closure interrupts learning and can pb to poor diet, stress and social isolation in children31,32,33. Dwelling confinement has strongly increased the rate of domestic violence in many countries, with a huge impact on women and children34,35, while information technology has too limited the access to long-term intendance such as chemotherapy, with substantial impacts on patients' health and survival chance36,37. Governments may have to await towards less stringent measures, encompassing maximum effective prevention simply enabling an acceptable residuum between benefits and drawbacks38.

Previous statistical studies on the effectiveness of lockdowns came to mixed conclusions. Whereas a relative reduction in R t of v% was estimated using a Bayesian hierarchical model19, a Bayesian mechanistic model estimated a reduction of fourscore% (ref. 20), although some questions take been raised regarding the latter work because of biases that overemphasize the importance of the almost recent measure out that had been implemented24. The susceptibility of other modelling approaches to biases resulting from the temporal sequence of NPI implementations remains to be explored. Our work tries to avoid such biases by combining multiple modelling approaches and points to a mild touch of lockdowns due to an overlap with furnishings of other measures adopted earlier and included in what is referred to every bit 'national (or full) lockdown'. Indeed, the national lockdown encompasses multiple NPIs (for example, closure of land, sea and air borders, closure of schools, non-essential shops and prohibition of gatherings and visiting nursing homes) that countries may accept already adopted in parts. From this perspective, the relatively attenuated impact of the national lockdown is explained as the petty delta after other concurrent NPIs have been adopted. This determination does not rule out the effectiveness of an early national lockdown, simply suggests that a suitable combination (sequence and time of implementation) of a smaller packet of such measures can substitute for a total lockdown in terms of effectiveness, while reducing agin impacts on society, the economic system, the humanitarian response system and the environment6,39,40,41.

Taken together, the social distancing and movement-restriction measures discussed above can therefore exist seen every bit the 'nuclear option' of NPIs: highly effective merely causing substantial collateral damages to society, the economy, trade and human rights4,39.

We find strong back up for the effectiveness of edge restrictions. The role of travelling in the global spread of respiratory diseases proved central during the starting time SARS epidemic (2002–2003)42, just travelling restrictions prove a large impact on trade, economy and the humanitarian response system globally41,43. The effectiveness of social distancing and travel restrictions is too in line with results from other studies that used different statistical approaches, epidemiological metrics, geographic coverage and NPI classification2,viii,9,10,11,thirteen,nineteen,xx.

We as well observe a number of highly effective NPIs that can exist considered less costly. For instance, nosotros find that risk-communication strategies characteristic prominently amongst consensus NPIs. This includes regime actions intended to educate and actively communicate with the public. The effective messages include encouraging people to stay at dwelling house, promoting social distancing and workplace safety measures, encouraging the self-initiated isolation of people with symptoms, travel warnings and information campaigns (mostly via social media). All these measures are non-binding regime advice, contrasting with the mandatory edge restriction and social distancing measures that are frequently enforced by constabulary or army interventions and sanctions. Surprisingly, communicating on the importance of social distancing has been only marginally less effective than imposing distancing measures by law. The publication of guidelines and work condom protocols to managers and healthcare professionals was likewise associated with a reduction in R t , suggesting that communication efforts too demand to exist tailored toward key stakeholders. Communication strategies aim at empowering communities with right information almost COVID-nineteen. Such measures tin can be of crucial importance in targeting specific demographic strata institute to play a dominant role in driving the spread of COVID-19 (for example, communication strategies to target individuals aged <40 years44).

Authorities food help programmes and other fiscal supports for vulnerable populations accept likewise turned out to be highly effective. Such measures are, therefore, not simply impacting the socio-economic sphere45 only also have a positive effect on public health. For instance, facilitating people'south access to tests or allowing them to self-isolate without fear of losing their job or part of their bacon may help in reducing R t .

Some measures are ineffective in (most) all methods and datasets—for example, ecology measures to disinfect and clean surfaces and objects in public and semi-public places. This finding is at odds with electric current recommendations of the WHO (World Health Organization) for ecology cleaning in non-healthcare settings46, and calls for a closer exam of the effectiveness of such measures. However, environmental measures (for instance, cleaning of shared surfaces, waste direction, approval of a new disinfectant, increased ventilation) are seldom reported by governments or the media and are therefore non collected by NPI trackers, which could atomic number 82 to an underestimation of their impact. These results call for a closer examination of the effectiveness of such measures. We besides find no show for the effectiveness of social distancing measures in regard to public send. While infections on buses and trains accept been reported47, our results may suggest a limited contribution of such cases to the overall virus spread, as previously reported48. A heightened public risk awareness associated with commuting (for example, people existence more likely to article of clothing face masks) might contribute to this finding49. Withal, we should note that measures aiming at limiting engorgement or increasing distancing on public ship accept been highly diverse (from complete counterfoil of all public transport to increase in the frequency of traffic to reduce traveller density) and could therefore pb to widely varying effectiveness, also depending on the local context.

The effectiveness of individual NPIs is heavily influenced by governance (Supplementary Information) and local context, every bit evidenced by the results of the entropic approach. This local context includes the stage of the epidemic, socio-economic, cultural and political characteristics and other NPIs previously implemented. The fact that gross domestic product is overall positively correlated with NPI effectiveness whereas the governance indicator 'vocalisation and accountability' is negatively correlated might be related to the successful mitigation of the initial stage of the epidemic of sure south-east Asian and Center East countries showing disciplinarian tendencies. Indeed, some south-east Asian government strategies heavily relied on the use of personal data and police sanctions whereas the Middle East countries included in our analysis reported depression numbers of cases in March–Apr 2020.

By focusing on individual countries, the what-if experiments using bogus land-specific sequences of NPIs offer a way to quantify the importance of this local context with respect to measurement of effectiveness. Our master takeaway hither is that the same NPI can have a drastically dissimilar impact if taken early on or later on, or in a different country.

It is interesting to annotate on the impact that 'enhancing testing capacity' and 'tracing and tracking' would have had if adopted at different points in time. Enhancing testing capacity should display a brusque-term increase in R t . Counter-intuitively, in countries testing close contacts, tracing and tracking, if they are effective, would have a similar effect on R t because more cases will be found (although tracing and tracking would reduce R t in countries that do not test contacts but rely on quarantine measures). For countries implementing these measures early, indeed, nosotros detect a short-term increase in R t (when the number of cases was sufficiently small to enable tracing and testing of all contacts). Nevertheless, countries implementing these NPIs later on did not necessarily detect more than cases, as shown by the respective subtract in R t . We focus on March and April 2020, a period in which many countries had a sudden surge in cases that overwhelmed their tracing and testing capacities, which rendered the respective NPIs ineffective.

Assessment of the effectiveness of NPIs is statistically challenging, because measures were typically implemented simultaneously and their impact might well depend on the particular implementation sequence. Some NPIs appear in almost all countries whereas in others only a few, pregnant that we could miss some rare but effective measures due to a lack of statistical power. While some methods might be decumbent to overestimation of the furnishings from an NPI due to bereft adjustments for confounding effects from other measures, other methods might underestimate the contribution of an NPI by assigning its touch on to a highly correlated NPI. Equally a consequence, estimates of ΔR t might vary essentially across unlike methods whereas agreement on the significance of individual NPIs is much more than pronounced. The strength of our study, therefore, lies in the harmonization of these four independent methodological approaches combined with the usage of an all-encompassing dataset on NPIs. This allows us to estimate the structural dubiousness of NPI effectiveness—that is, the dubiety introduced by choosing a certain model structure likely to affect other modelling works that rely on a single method just. Moreover, whereas previous studies oftentimes subsumed a wide range of social distancing and travel restriction measures under a single entity, our analysis contributes to a more fine-grained understanding of each NPI.

The CCCSL dataset features non-homogeneous information completeness across the different territories, and data collection could exist biased by the data collector (native versus non-native) as well as by the information communicated past governments (run across besides ref. 23). The WHO-PHSM and CoronaNet databases contain a broad geographic coverage whereas CCCSL focuses mostly on developed countries. Moreover, the coding system presents certain drawbacks, notably because some interventions could belong to more than one category just are recorded only once. Compliance with NPIs is crucial for their effectiveness, yet we causeless a comparable degree of compliance by each population. Nosotros tried to mitigate this issue by validating our findings on two external databases, even if these are subject field to similar limitations. We did not perform a formal harmonization of all categories in the three NPI trackers, which limits our ability to perform full comparisons among the three datasets. Additionally, nosotros neither took into account the stringency of NPI implementation nor the fact that not all methods were able to describe potential variations in NPI effectiveness over time, likewise the dependency on the epidemic historic period of its adoption. The time window is limited to March–April 2020, where the construction of NPIs is highly correlated due to simultaneous implementation. Future research should consider expanding this window to include the period when many countries were easing policies, or possibly fifty-fifty strenghening them once again afterward easing, as this would allow clearer differentiation of the correlated structure of NPIs because they tended to be released, and implemented again, 1 (or a few) at a time.

To compute R t , we used time serial of the number of confirmed COVID-nineteen cases50. This approach is likely to over-stand for patients with severe symptoms and may be biased by variations in testing and reporting policies amid countries. Although we assume a constant serial interval (average timespan between primary and secondary infection), this number shows considerable variation in the literature51 and depends on measures such as social distancing and self-isolation.

In decision, hither nosotros present the consequence of an extensive analysis on the impact of 6,068 private NPIs on the R t of COVID-19 in 79 territories worldwide. Our assay relies on the combination of three big and fine-grained datasets on NPIs and the apply of iv independent statistical modelling approaches.

The emerging moving picture reveals that no ane-size-fits-all solution exists, and no single NPI tin decrease R t below ane. Instead, in the absenteeism of a vaccine or efficient antiviral medication, a resurgence of COVID-xix cases can be stopped simply by a suitable combination of NPIs, each tailored to the specific country and its epidemic historic period. These measures must be enacted in the optimal combination and sequence to be maximally effective against the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and thereby enable more rapid reopening.

Nosotros showed that the most effective measures include closing and restricting most places where people assemble in smaller or larger numbers for extended periods of time (businesses, bars, schools and so on). All the same, we too find several highly effective measures that are less intrusive. These include land border restrictions, governmental support to vulnerable populations and risk-advice strategies. We strongly recommend that governments and other stakeholders beginning consider the adoption of such NPIs, tailored to the local context, should infection numbers surge (or surge a 2d time), before choosing the most intrusive options. Less drastic measures may too foster ameliorate compliance from the population.

Notably, the simultaneous consideration of many distinct NPI categories allows us to move beyond the simple evaluation of individual classes of NPIs to appraise, instead, the commonage touch on of specific sequences of interventions. The ensemble of these results calls for a strong effort to simulate what-if scenarios at the country level for planning the most probable effectiveness of time to come NPIs, and, thank you to the possibility of going down to the level of individual countries and country-specific circumstances, our arroyo is the first contribution toward this end.

Methods

Data

NPI data

We apply the publicly available CCCSL dataset on NPIs23, in which NPIs are categorized using a four-level hierarchical coding scheme. L1 defines the theme of the NPI: 'case identification, contact tracing and related measures', 'ecology measures', 'healthcare and public wellness capacity', 'resource allocation', 'returning to normal life', 'gamble communication', 'social distancing' and 'travel brake'. Each L1 (theme) is composed of several categories (L2 of the coding scheme) that contain subcategories (L3), which are further subdivided into group codes (L4). The dataset covers 56 countries; data for the Usa are available at the country level (24 states), making a total of 79 territories. In this analysis, nosotros employ a static version of the CCCSL, retrieved on 17 August 2020, presenting 6,068 NPIs. A glossary of the codes, with a detailed clarification of each category and its subcategories, is provided on GitHub. For each land, nosotros apply the data until the twenty-four hour period for which the measures have been reliably updated. NPIs that take been implemented in fewer than five territories are not considered, leading to a final total of 4,780 NPIs of 46 different L2 categories for use in the analyses.

Second, we utilise the CoronaNet COVID-19 Authorities Response Event Dataset (v.1.0)27 that contains 31,532 interventions and covers 247 territories (countries and US states) (data extracted on 17 August 2020). For our analysis, we map their columns 'type' and 'type_sub_cat' onto L1 and L2, respectively. Definitions for the entire 116 L2 categories tin can be institute on the GitHub page of the projection.

Using the same criterion as for the CCCSL, we obtain a final total of 18,919 NPIs of 107 dissimilar categories.

Third, nosotros use the WHO-PHSM dataset26, which merges and harmonizes the following datasets: ACAPS41, Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker52, the Global Public Wellness Intelligence Network (GPHIN) of Public Health Agency of Canada (Ottawa, Canada), the CCCSL23, the United States Centers for Disease Command and Prevention and Hit-COVID53. The WHO-PHSM dataset contains 24,077 interventions and covers 264 territories (countries and US states; data extracted on 17 August 2020). Their encoding scheme has a heterogeneous coding depth and, for our analysis, we map 'who_category' onto L1 and either accept 'who_subcategory' or a combination of 'who_subcategory' and 'who_measure' as L2. This results in twoscore mensurate categories. A glossary is available at: https://world wide web.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/phsm.

The CoronaNet and WHO-PHSM datasets as well provide information on the stringency of the implementation of a given NPI, which we did not use in the current study.

COVID-19 case data

To approximate R t and growth rates of the number of COVID-19 cases, we use time series of the number of confirmed COVID-xix cases in the 79 territories considered50. To control for weekly fluctuations, we smooth the time series by computing the rolling boilerplate using a Gaussian window with a standard divergence of 2 days, truncated at a maximum window size of xv days.

Regression techniques

Nosotros apply iv different statistical approaches to quantify the impact of a NPI, M, on the reduction in R t (Supplementary Information).

CC

Case-command analysis considers each single category (L2) or subcategory (L3) 1000 separately and evaluates in a matched comparison the difference, ΔR t , in R t betwixt all countries that implemented K (cases) and those that did not (controls) during the ascertainment window. The matching is done on epidemic age and the fourth dimension of implementation of any response. The comparison is fabricated via a linear regression model adjusting for (1) epidemic age (days later the country has reached 30 confirmed cases), (2) the value of R t before M takes effect, (iii) total population, (4) population density, (v) the total number of NPIs implemented and (six) the number of NPIs implemented in the same category equally Yard. With this design, we investigate the time filibuster of τ days betwixt implemention of M and ascertainment of ΔR t , also as additional country-based covariates that quantify other dimensions of governance and human and economic development. Estimates for R t are averaged over delays between 1 and 28 days.

Stride function Lasso regression

In this approach we assume that, without whatsoever intervention, the reproduction gene is abiding and deviations from this constant effect from a delayed onset by τ days of each NPI on L2 (categories) of the hierarchical dataset. Nosotros utilize a Lasso regularization arroyo combined with a meta parameter search to select a reduced fix of NPIs that best draw the observed ΔR t . Estimates for the changes in ΔR t attributable to NPI M are obtained from country-wise cross-validation.

RF regression

We perform a RF regression, where the NPIs implemented in a country are used as predictors for R t , time-shifted τ days into the future. Hither, τ accounts for the time delay between implementation and onset of the effect of a given NPI. Similar to the Lasso regression, the assumption underlying the RF approach is that, without changes in interventions, the value of R t in a territory remains constant. However, contrary to the two methods described above, RF represents a nonlinear model, meaning that the effects of individual NPIs on R t do non need to add upwardly linearly. The importance of a NPI is defined as the pass up in predictive performance of the RF on unseen data if the data apropos that NPI are replaced by racket, also called permutation importance.

Transformer modelling

Transformers54 have been demonstrated as models suitable for dynamic discrete chemical element processes such equally textual sequences, due to their power to recall past events. Here we extended the transformer architecture to approach the continuous case of epidemic information by removing the probabilistic output layer with a linear combination of transformer output, whose input is identical to that for RF regression, along with the values of R t . The all-time-performing network (least hateful-squared error in country-wise cantankerous-validation) is identified as a transformer encoder with 4 hidden layers of 128 neurons, an embedding size of 128, eight heads, one output described by a linear output layer and 47 inputs (respective to each category and R t ). To quantify the impact of measure 1000 on R t , we apply the trained transformer as a predictive model and compare simulations without whatever measure (reference) to those where ane measure is presented at a fourth dimension to assess ΔR t . To reduce the furnishings of overfitting and multiplicity of local minima, we study results from an ensemble of transformers trained to like precision levels.

Estimation of R t

We utilize the R packet EpiEstim55 with a sliding time window of vii days to estimate the fourth dimension serial of R t for every country. We choose an uncertain serial interval following a probability distribution with a mean of iv.46 days and a standard deviation of ii.63 days56.

Ranking of NPIs

For each of the methods (CC, Lasso regression and TF), we rank the NPI categories in descending order co-ordinate to their impact—that is, the estimated degree to which they lower R t or their feature importance (RF). To compare rankings, we count how many of the 46 NPIs considered are classified as belonging to the top 10 ranked measures in all methods, and test the null hypothesis that this overlap has been obtained from completely independent rankings. The P value is then given by the complementary cumulative distribution function for a binomial experiment with 46 trials and success probability (x/46)4. We study the median P value obtained over all x ≤ x to ensure that the results are non dependent on where we impose the cut-off for the classes.

Co-implementation network

If there is a statistical tendency that a country implementing NPI i also implements NPI j later in time, we depict a direct link from i to j. Nodes are placed on the y axis according to the average epidemic historic period at which the corresponding NPI is implemented; they are grouped on the x axis by their L1 theme. Node colours correspond to themes. The effectiveness scores for all NPIs are re-scaled between cipher and one for each method; node size is proportional to the re-scaled scores, averaged over all methods.

Entropic country-level approach

Each territory tin can exist characterized by its socio-economic conditions and the unique temporal sequence of NPIs adopted. To quantify the NPI effect, nosotros measure the heterogeneity of the overall rank of a NPI among the countries that have taken that NPI. To compare countries that have implemented different numbers of NPIs, we consider the normalized rankings where the ranking position is divided by the number of elements in the ranking list (that is, the number of NPIs taken in a specific state). We and so bin the interval [0, one] of the normalized rankings into ten sub-intervals and compute for each NPI the entropy of the distribution of occurrences of that NPI in the different normalized rankings per country:

$$S(\mathrm{NPI}\,)=-\frac{one}{\mathrm{log}\,(10)}\sum _{i}{P}_{i}\mathrm{log}\,({P}_{i}),$$

(1)

where P i is the probability that the NPI considered appeared in the ith bin in the normalized rankings of all countries. To assess the confidence of these entropic values, results are compared with expectations from a temporal reshuffling of the data. For each country, we keep the same NPIs adopted merely reshuffle the fourth dimension stamps of their adoption.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The CCCSL dataset tin exist downloaded from http://covid19-interventions.com/. The CoronaNet data tin exist found at https://www.coronanet-project.org/. The WHO-PHSM dataset is bachelor at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/phsm. Snapshots of the datasets used in our report are available in the following github repository: https://github.com/complexity-science-hub/ranking_npis.

Lawmaking availability

Custom code for the assay is available in the following github repository: https://github.com/complexity-science-hub/ranking_npis.

References

-

Qualls, Due north. L. et al. Customs mitigation guidelines to forestall pandemic influenza – U.s., 2017. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 66, i–34 (2017).

-

Tian, H. et al. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first l days of the COVID-19 epidemic in Cathay. Science 368, 638–642 (2020).

-

Chen, South. et al. COVID-19 command in China during mass population movements at New year. Lancet 395, 764–766 (2020).

-

Lee, Grand., Worsnop, C. Z., Grépin, K. A. & Kamradt-Scott, A. Global coordination on cross-edge travel and trade measures crucial to COVID-19 response. Lancet 395, 1593–1595 (2020).

-

Chakraborty, I. & Maity, P. Covid-19 outbreak: migration, furnishings on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 728, 138882 (2020).

-

Pfefferbaum, B. & North, C. S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Eng. J. Med. 383, 510–512.

-

COVID-19 dashboard past the Eye for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University of Medicine (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, accessed 4 June 2020); https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

-

Chinazzi, K. et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2022 novel coronavirus (COVID-xix) outbreak. Scientific discipline 368, 395–400 (2020).

-

Arenas, A., Cota, W., Granell, C. & Steinegger, B. Derivation of the effective reproduction number R for COVID-nineteen in relation to mobility restrictions and solitude. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20054320 (2020).

-

Wang, J., Tang, K., Feng, K. & Lv, West. When is the COVID-19 pandemic over? Prove from the stay-at-abode policy execution in 106 Chinese cities. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3561491 (2020).

-

Soucy, J.-P. R. et al. Estimating effects of physical distancing on the COVID-19 pandemic using an urban mobility alphabetize. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/x.1101/2020.04.05.20054288 (2020).

-

Anderson, S. C. et al. Estimating the touch of Covid-xix control measures using a Bayesian model of concrete distancing. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.17.20070086 (2020).

-

Teslya, A. et al. Bear on of cocky-imposed prevention measures and short-term authorities intervention on mitigating and delaying a COVID-19 epidemic. PLoS Med. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003166 (2020).

-

Kraemer, M. U. et al. The effect of human mobility and command measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in Communist china. Science 497, 493–497 (2020).

-

Prem, K. & Liu, Y. et al. The consequence of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling report. Lancet Public Wellness 5, e261–e270 (2020).

-

Gatto, M. et al. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-nineteen epidemic in Italian republic: effects of emergency containment measures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10484–10491 (2020).

-

Lorch, Fifty. et al. A spatiotemporal epidemic model to quantify the furnishings of contact tracing, testing, and containment. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.07641 (2020).

-

Dehning, J. & Zierenberg, J. et al. Inferring change points in the spread of COVID-19 reveals the effectiveness of interventions. Science 369, eabb9789 (2020).

-

Banholzer, N. et al. Touch of not-pharmaceutical interventions on documented cases of COVID-19. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.xvi.20062141 (2020).

-

Flaxman, Southward. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 584, 257–261 (2020).

-

Hsiang, South. et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-nineteen pandemic. Nature 584, 262–267 (2020).

-

Nachega, J., Seydi, Yard. & Zumla, A. The late arrival of coronavirus disease 2022 (Covid-nineteen) in Africa: mitigating pan-continental spread. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 875–878 (2020).

-

Desvars-Larrive, A. et al. A structured open up dataset of authorities interventions in response to COVID-19. Sci. Data 7, 285 (2020).

-

Bryant, P. & Elofsson, A. The limits of estimating COVID-19 intervention furnishings using Bayesian models. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ten.1101/2020.08.14.20175240 (2020).

-

Protecting People and Economies: Integrated Policy Responses to COVID-19 (World Bank, 2020); https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33770

-

Tracking Public Health and Social Measures: A Global Dataset (Globe Wellness Organization, 2020); https://world wide web.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/phsm

-

Cheng, C., Barceló, J., Hartnett, A. S., Kubinec, R. & Messerschmidt, 50. COVID-19 government response event dataset (CoronaNet 5.1.0). Nat. Hum. Behav. four, 756–768 (2020).

-

Auger, K. A. et al. Association between statewide school closure and COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the The states. JAMA 324, 859–870 (2020).

-

Liu, Y. et al. The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on SARS-CoV-2 transmission across 130 countries and territories. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ten.1101/2020.08.11.20172643 (2020).

-

Park, Y., Choe, Y. et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 2465–2468(2020).

-

Adverse Consequences of School Closures (UNESCO, 2020); https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences

-

Educational activity and COVID-19: Focusing on the Long-term Bear upon of School Closures (OECD, 2020); https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/education-and-covid-xix-focusing-on-the-long-term-bear on-of-school-closures-2cea926e/

-

Orben, A., Tomova, 50. & Blakemore, Southward.-J. The effects of social deprivation on boyish development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Wellness 4, 634–640 (2020).

-

Taub, A. A new covid-xix crisis: domestic abuse rises worldwide. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html (6 April 2020).

-

Abramian, J. The Covid-xix pandemic has escalated domestic violence worldwide. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackieabramian/2020/07/22/the-covid-19-pandemic-has-escalated-global-domestic-violence/#57366498173e (22 July 2020).

-

Tsamakis, K. et al. Oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges, dilemmas and the psychosocial impact on cancer patients (review). Oncol. Lett. 20, 441–447 (2020).

-

Raymond, Eastward., Thieblemont, C., Alran, Southward. & Faivre, S. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the management of patients with cancer. Target. Oncol. 15, 249–259 (2020).

-

Couzin-Frankel, J., Vogel, G. & Weiland, M. School openings beyond world suggest ways to keep coronavirus at bay, despite outbreaks. Science https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/school-openings-across-globe-suggest-ways-proceed-coronavirus-bay-despite-outbreaks# (2020).

-

Vardoulakis, S., Sheel, M., Lal, A. & Greyness, D. Covid-nineteen environmental transmission and preventive public wellness measures. Aust. Northward. Z. J. Public Health 44, 333–335 (2020).

-

Saadat, S., Rawtani, D. & Hussain, C. M. Environmental perspective of Covid-19. Sci. Total Environ. 728, 138870 (2020).

-

Covid-nineteen Government Measures Dataset (ACAPS, 2020); https://www.acaps.org/covid19-government-measures-dataset

-

Brockmann, D. & Helbing, D. The hidden geometry of complex, network-driven contagion phenomena. Science 342, 1337–1342 (2013).

-

Guan, D. et al. Global supply-chain effects of Covid-19 command measures. Nat. Hum. Behav. four, 577–587 (2020).

-

Malmgren, J., Guo, B. & Kaplan, H. G. Covid-19 confirmed case incidence age shift to young persons anile 0–nineteen and 20–39 years over time: Washington Land March–April 2020. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.21.20109389 (2020).

-

Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Orton, I. & Dale, P. Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-nineteen (World Bank, 2020); https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33635

-

Cleaning and Disinfection of Environmental Surfaces in the Context of COVID-19 (Earth Health Organization, 2020); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/cleaning-and-disinfection-of-ecology-surfaces-inthe-context-of-covid-19

-

Shen, J. et al. Prevention and command of COVID-19 in public transportation: experience from Mainland china. Environ. Pollut. 266, 115291 (2020).

-

Islam, N. et al. Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus affliction 2019: natural experiment in 149 countries. BMJ 370, m2743 (2020).

-

Liu, X. & Zhang, South. Covid-19: confront masks and human-to-human transmission. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 14, 472–473 (2020).

-

2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-nineteen (2019-nCoV) Information Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, 2020); https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19

-

Griffin, J. et al. A rapid review of available evidence on the serial interval and generation fourth dimension of COVID-19. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ten.1101/2020.05.08.20095075 (2020).

-

Unhurt, T., Webster, S., Petherick, A., Phillips, T. & Kira, B. Oxford COVID-19 Regime Response Tracker (Blavatnik Schoolhouse of Government & University of Oxford, 2020); https://world wide web.bsg.ox.air-conditioning.uk/inquiry/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker

-

Zheng, Q. et al. Striking-COVID, a global database tracking public health interventions to COVID-19. Sci. Data seven, 286 (2020).

-

Vaswani, A. et al. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems thirty (eds Guyon, I. et al.) 5998–6008 (Curran Associates, 2017).

-

Cori, A., Ferguson, N. M., Fraser, C. & Cauchemez, S. A new framework and software to estimate fourth dimension-varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 178, 1505–1512 (2013).

-

Valka, F. & Schuler, C. Interpretation and interactive visualization of the fourth dimension-varying reproduction number R t and the time-delay from infection to interpretation. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.19.20197970 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Roux for her contribution to the coding of the interventions recorded in the dataset used in this study. We thank D. Garcia, V. D. P. Servedio and D. Hofmann for their contribution in the early on stage of this work. Due north.H. thanks L. Haug for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Promotion Agency, the FFG project (no. 857136), the WWTF (nos. COV twenty-001, COV twenty-017 and MA16-045), Medizinisch-Wissenschaftlichen Fonds des Bürgermeisters der Bundeshauptstadt Wien (no. CoVid004) and the project VET-Austria, a cooperation between the Austrian Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Intendance and Consumer Protection, the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety and the Academy of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna. The funders had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, conclusion to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

Northward.H., L.G., A.Fifty., V.50. and P.One thousand. conceived and performed the analyses. 5.50., Southward.T. and P.M. supervised the study. Eastward.D. contributed additional tools. N.H., L.Yard., A.L., A.D.-Fifty., B.P. and P.K. wrote the first draft of the newspaper. A.D.-L. supervised data collection on NPIs. All authors discussed the results and contributed to revision of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Peer review information Peer review reports are bachelor. Primary handling editor: Stavroula Kousta.

Publisher's note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Haug, N., Geyrhofer, 50., Londei, A. et al. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 regime interventions. Nat Hum Behav 4, 1303–1312 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Result Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0

Further reading

woodberryaphis1992.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-01009-0

0 Response to "Which of the Following Measures Can Only Government Action Effectively Implement?"

Postar um comentário